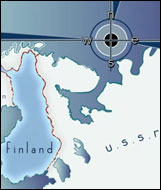

Preparations for the War

In the first week of June 1941, long range patrols were sent by the

Finns into the Karelian Isthmus areas to scout out Soviet defenses

and positions. On June 6, German troops began to unload in Finland,

the main German forces started to arrive at the Finn port of Pohjanmaa.

By the June 15, the Germans were granted the right to operate in

the Lapland area of Finland. Finnish troops in the area were placed

under German control. In this same time frame, some Finnish patrols

reached as deep as Viipuri (known at the time and now as Vyborg,

Russia).

The Finnish Army is mobilized on the June 17 and 475,000 Finn soldiers were ready for battle by the end of the month. On June 20, civilians were moved from border areas, mainly due to the efforts of the Finnish border guards. On the June 21-22, Finnish and German naval forces begin to mine the areas around Finland, with one Finnish submarine mining the areas around Estonia.

The War Begins

When Germany attacked the Soviet Union on June 2, 1941, Finland declared

itself neutral, but there were German bombers using Finnish bases

to refuel their planes and using Finnish air space to attack points

inside the Soviet Union. There were also German troops in the Lapland

area that moved to take the town of Petsamo. Inside the Finnish

borders the Soviet base at Hanko fired on the Finnish Navy and

the Red Army Air Force hit at least 15 different target areas.

By the June 25, after a massive Soviet air strike, Finland had

stated that the Soviet Union had declared war, and that Finland

must once again defend itself from the Soviet threat. Mannerheim

moved his headquarters to Mikkeli, which is the same location used

during the Winter War. By the end of June there were some Finnish-Soviet

border clashes, and the German soldiers had moved from Lapland

across the Soviet border. The Finnish Independent Detachment Petsamo

was attached to German units. Their goal was to push toward Murmansk

and the key areas around this Soviet city.

First Attacks

Mannerheim decided the best place to strike

was against the Soviet forces in the area of Ladoga-Karelia and not

towards Leningrad

and the Karelian Isthmus. He ordered the attacks to begin on July

9. The Finnish forces went forward, and within a week’s time

met with success. One of the main reasons for this success was

that, unlike the Winter War, the Finns enjoyed numerical superiority

over the Red Army in this region. The Finnish soldiers were also

well commanded and well trained. The lessons learned during the

Winter War showed on the battlefield. The Finnish forces were successful

in splitting the Soviets in two and there were Finnish commanders

who wished to push the attack forward to the Svir River. However,

Mannerheim stopped the advance telling his commanders to hold in

place. By August 23 the Finns had captured Suojärvi which

was the last holdout in the region.

The Isthmus

On July 30, the Finns began their attacks on the Karelian Isthmus

with the attacks centered between Simpele and Rautjärvi. The

main goal of this offensive was to take back Viipuri and move into

key positions on the Isthmus. The first main attack was in the

area of Hiitola and the aim was to cut off supply and communication

between the Soviet forces in the area of Ladoga. The fighting in

this region was hard and there was loss of life on all sides during

these battles. Still the Finns were able to advance quickly and

retook Viipuri by August 29. The Finnish advances threatened to

encircle and trap the Soviets defending the city, so the Soviets

decided that a retreat was the only way to survive. This victory

was important to the Finns. The famous city had been lost during

the Winter War. It was a city that meant a lot to the Finns, symbolically

at least. By September, the Finns had moved into the area of the

old 1939 border and stopped in place. In some cases they did advance

past the old border but this was to take advantage of natural terrain

improving Finnish defensive positions.

North of Lake Ladoga

For the most part, the fighting above Lake Ladoga was going well

for the Finns, but the same could not be said for the German forces.

The German attacks towards Murmansk were stalling as the Soviet

resistance was greater than expected. Still, the Finns had met

their goals in the region and the areas of Karelia that had been

lost to the Soviets in the Winter War had been retaken (but for

Hanko). The question the Finns began to face at this point was

how far they would go into Soviet territory. The question had not

been addressed before the fighting started. This was a very big

question, and one the Finns could not take lightly. They had entered

the war stating their goal was to retake the land lost in the Winter

War and it had been done. If they did go further, just how much

further would they be willing to go? After a debate, it was decided

the Finns must advance in Karelia to allow a better defensive position.

This would also assist in stopping Soviet bombing of Finland from

bases in these areas.

Eastern Karelia

On September 4, the operations that would lead to the Finnish occupation

of areas of Eastern Karelia began. The first attacks were in the

general direction of the Svir River. On the right flank of the

Karelian Army there quickly followed a strike of the armored division.

The target was the village of Aunus, which fell on the September

5. The Soviet positions on the Svir River were taken by the September

7-9. The Finns crossed to the other side of the river to make use

of the better roads located on the opposite riverbank. As such,

the Finns were approximately 12 miles on the other side of the

river on a 60-mile front – starting at the city of Osta and

running to the west from that location. The left flank of the Karelian

Army also began its advance on the September 14-15 with its goal

being the capitol of Eastern Karelia, Petrozavodsk. The fighting

was hard in this time frame but by October 10, the Soviets left

the city to the Finnish Army. The next Finnish operation was undertaken

just after the fall of Petrozavodsk, and the goal was to improve

and secure defensive positions between Lake Onega and Lake Segozero.

The city of Medvezh’egorsk was also a major target goal of

the Finns. Mannerheim wanted to push this attack quickly but the

fighting was quite hard. The land area was tough to control and

the Soviet defenders put up a bitter defense. However, by December

5, this area was secured by the Finns. The result of this attack

gave the Finns major control points on the Maaselkä Isthmus.

The Finnish attacks and success in this region were problematic to the Soviets. This advance threatened Leningrad and was seen as a very real threat to cut the Murmansk railroad. If this was done, supplies that were greatly needed by the Soviet Union would be cut off. This was so dire that if the railroad was cut off, the war might end with a German victory. Much of the allied aid going to the interior of the Soviet Union, as well as aid from a still non-combatant United States, was coming via this railway. A section of this railway had already been cut by the Finns in their attacks in Eastern Karelia.

Stalin began to pressure Churchill to assist in stopping the Finnish advance. He hoped the threat of Great Britain declaring war on Finland might halt the Finns. Churchill sent a personal letter to Mannerheim on December 1, asking for the Finnish advance to be halted. Churchill informed Mannerheim that unless the Finnish actions were stopped that England would be forced to declare war on Finland. While it is clear that Mannerheim both respected and liked Churchill, he felt the attacks had to continue to strengthen the Finnish positions. England declared war on Finland on December 6. Interestingly, the Finns were in the process of halting their advances when England declared war but, Churchill was not informed.

Mannerheim told the Germans that a Finnish attack on the Murmansk area was pending but, it seemed these plans were to be halted. The reasons were mainly political. The Finns were also faced with the fact the U.S. might declare war on Finland, which had been threatened if the Murmansk railway was cut. Mannerheim was also worried that if the Germans were to lose the war this advance might be costly later in terms of Finnish lives. On December 6, the Soviets started to counterattack the Germans which halted their advance towards Moscow and this did not encourage the Finns’ feelings about German success in the war. The Finns had done few joint military operations with the Germans up to this point and more joined actions seemed unlikely.

Finland was again in a difficult position as the Germans pressed the Finns to increase their attacks. There was no possibility of the Finns directly attacking Leningrad, which was a bone of contention with the Germans. The Finns knew that an attack on Leningrad would not be forgiven by the Soviets. Had the Finns attacked Leningrad and the Germans were to still lose the war, the Soviet retributions on the Finns would have been quite harsh. This was the same attitude the Finns took in the areas of the White Sea as their advances were halted. Additional Finnish offensive operations would be too costly in political terms in case the war turned against them. There was also only mild support in the Finnish population for more aggressive actions, since the Finns felt their war goals had been a success. Any further gains would seem more a war of aggression and conquest, not a continuation of the Winter War. There were also the losses. The Finns lost 25,475 killed or wounded, by the end of December. Part of these losses came in a large Soviet counteract on the Svir River near the city of Gora where the Soviet 114th Division attempted to push the Finnish lines. There was still some talk about Finn/German joint attacks but the chances of these began to fade as Mannerheim lost confidence in the German command.

This was to end the Finnish offensive stage of the Continuation War. The Finns slowly started to let older men leave army service and return to home, while all those soldiers of fighting age began to dig in for what was to come.