The Finns had expected and anticipated a Soviet attack from the south, through the Karelian Isthmus. Finnish commanders mobilized the armed forces in September and October and began preparing their defensive line, called the Mannerheim Line, three to four months in advance of the outbreak of war. If not for this early mobilization, Soviet troops would have likely easily broken through.

In the north, geography greatly helped the Finns. Although Finnish commanders were surprised by the Soviet attack through this mostly wilderness area, the few passable roads made the terrain unsuitable for mechanized warfare.

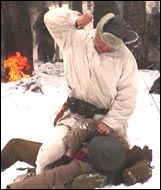

The weather also favored the Finns. The winter of 1939 was one of the coldest in history, making it difficult for machinery to operate. Finns knew the terrain and were prepared for the weather conditions. They dressed in white camouflage, making themselves virtually invisible to Soviet troops.

The terrain and the weather favored highly mobile, small unit tactics developed by the Finns. By striking the front and rear of the long, single files of the Soviet mechanized columns, they were able to stop them, trap them and then with hit and run raids on skis, chop them into smaller and smaller pieces. These so-called motti (the Finnish word for a cord of firewood) tactics, in the forests of northern Finland, in sub-zero weather, neutralized the Soviets’ numeric and technological strengths.

Finnish Troops

Ben Strout"Belaya smert" was a Russian

term for the Finnish snipers. The term means "white death".

The Finnish army had white uniforms which allowed them to blend into

the countrysides and deep forrest of the war zone. With their training

in extreame cold survival, the "belaya smert" were able

to wait for long periods of time for the perfect target.

Another strategic advantage for the Finns came from their unity of purpose and their high morale. Finns knew that the war was a fight for their national survival. All segments of Finnish society banded together against a common enemy. Thus, they endured constant air raids, unceasing artillery barrages, the winter cold and the numerous casualties of the war.

In the end, however, the Soviet Union’s vast army and virtually infinite resources beat down Finland's spirited resistance. Yet, the Finnish Army was able to punish the Red Army sufficiently and hold out long enough so that Soviet Party leaders saw the wisdom of a negotiated settlement.

Finland’s military leader, Field Marshall Mannerheim summed up the Winter War experience in his memoirs:

The one lesson above all that I wish to stamp on the consciousness of the next generation is this: fractiousness in one's own ranks is more deadly than the enemy's sword, and internal discord opens the door to the outside aggressor. The people of Finland have shown in two wars that a united nation, small though it may be, can develop unprecedented fighting power and thus withstand the most formidable ordeals that destiny brings.

By closing ranks at the moment of peril the people of Finland earned for themselves the right to continue to live their own independent lives within the family of free peoples. They did not waver in their efforts: they were made of sound and sturdy stuff. If we remain faithful to ourselves and if, at all moments of destiny, we cling unanimously and unfalteringly to the values which to this day have been the foundation of Finland's freedom -- the faith inherited from our fathers, the love of our homeland and the determination and intrepid readiness to defend it -- then the people of Finland can look to the future with the firmest of confidence."